Charting the “Enchanted Isles”

Joseph R. Slevin

Slevin's use of English island names is left as is. The first occurrence of a ship's name provides a link to information about that ship (if available) on our “Ships” page. A § or † symbol indicates a footnote added to this online page, and word(s) {within braces} are likewise added.

There can be little doubt that the Galápagos Archipelago or the “Enchanted Isles,” as they were called by the Spaniards, is one of the most remarkable spots, speaking from a zoological standpoint, that can be found in this world of ours. For those who are not familiar with the position of this “zoological paradise” made famous by Charles Darwin, who visited it in 1835 as a naturalist with His Britannic Majesty's Ship Beagle on its cruise to South America, it can easily be placed by picturing one's self on the coast of Ecuador and then following the equator some 500 miles out to sea. Mount Pitt on Chatham Island, the easternmost one of the group, is 502.5 miles northwest of Marlin-spike Rock, Cape San Lorenzo, Ecuador. §

§ Mt. Pitt is actually about 575 miles west of Cabo San Lorenzo.

The Archipelago consists of some fifteen islands and numerous islets and rocks extending from Latitude 1° 40' N to 1° 26' S and from Longitude 89° 16' 58” to 92° 1' W. Albemarle, shaped somewhat like a boot, is the largest of the group, being approximately seventy miles in length and forty five in breadth at the southern end, the widest part. Narborough, James, Indefatigable, Chatham, Charles, Bindloe, Abingdon, Tower and Hood, respectively, are next in size and importance, while the remainder range from islets of a mile or less to mere rocks.

The position of the Galápagos Archipelago was fairly well known to the early navigators. Bishop Tomás de Berlanga, carried there by strong currents while on a voyage from Panama to Peru in 1535, took the latitude and placed the islands between half a degree and a degree and a half south of the equator. He was not far off in his calculations as the main portion of the Archipelago does extend 1° 25' south of the equator. Early navigators placed the islands about two degrees west of the 80th meridian; but Dampier, one of the buccaneers, claimed they were farther to the west and in this he was correct, for the main portion lies west of the 90th meridian and all of it west of the 89th. Mercator in his “Orbis Terrarum Compendiosa Descriptio” of 1587 represented the Galápagos as a cluster of islets just above the equator and in his Map of the New World, 1622, as just below it.§ {Gabriel} Tatton's map of 1600 showed the Archipelago as just below the equator and Herrar's§§ map of 1601 is practically identical. None of the cartographers seemed to doubt that the islands were on or close to the equator.

§ Mercator (1512-1594) placed two island groups on his 1569 Nova et aucta orbis terrae descriptio ed usum navigantium emendate accomodata, both above the equator. By 1622 he had been dead for 28 years, so the identity (and actual name) of his “Map of the New World” is unclear.

§§ Probably, Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas; Historia general de los hechos de los Castellanos en las Islas i Tierra Firme del Mar Océano.

The islands appeared on Ortelius' “Theatrum Orbis Terrarum,” published at Antwerp in 1570, as Insulae de los Galopegos§ and in his 'Peruviae Auriferae Regionis Typus” of 1574 as Isolas de Galápagos, represented as one island with two adjacent islets. The Chinese Maps of the World published by the Jesuit Father Matteo Ricci (1584-1608) showed an area labeled “South Seas” with a group of islands in the approximate position of the Galápagos, though no name was given them.§§ After 1570 the islands appeared on many maps of the early cartographers but without names. No attempt was made to attach individual names until William Ambrose Cowley made his chart in 1684.†

§ The islands appeared as Ins. de los galepegos and also as Ins. de los galopegos.

§§ The islands are absent on Ricci's 1602 map, but appear on a ca. 1604 Japanese copy.

† Although Cowley visited the islands in 1684, his chart was published by Herman Moll in 1699.

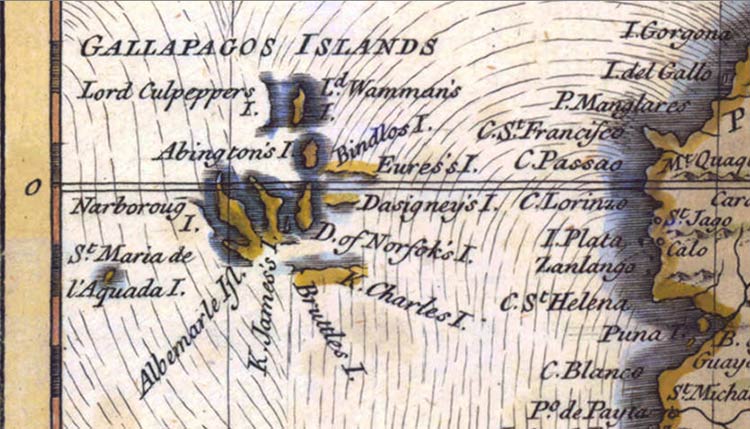

From a study of Cowley's map, the islands can be properly placed. The large bight on the west coast of Duke of Norfolk Island [Indefatigable] marked “Sandy Beach” is Conway Bay and this gives a fix for Duncan Island, though that island is a little off position. Albemarle and James are decidedly off. Taking this into consideration one can see that Duncan Island is the Sir Anthony Deans* Island of Cowley. His chart located the following islands: The Duke of Albemarle's Island, The Earl of Abingdon's Island, Captain Bindlos's Island, Brattles Island, King Charles's Island, Crossman's Island, Lord Culpeper's Island, Dassigney's Island [Chatham], Sir Anthony Dean's Island [Duncan], Ewres Island [Tower], King James's Island, Sir John Narbrough Island, Duke of Norfolk's Island [Indefatigable], Lord Wenman's Island, Albanie Island, and Cowley's Inchanted Island.

* A famous shipwright in the reign of King Charles II.

A map printed for H. Moll of London in 1744 entitled “A Map of South America with all the European Settlements and [sic, &] whatever else is remarkable from the latest and [sic, &] best observations” § shows the islands in their relative positions and gives the old English names, as does a chart by Samuel Dunn printed in 1787 {and published} by Laurie and Whittle of London.§§ A chart with no more identifying data than the name “Nueva y Correcta Carta Del Mar Pacifico ó del Sur,” dated 1744, shows some twelve islands and uses the old Spanish names, such as Isla de Esperanza, San Clemente, Isabel, Carenero, and Maria del Aguado [sic, Aguada].† With the exception of Isabel [Albemarle] it is impossible to identify them by comparing them with a modern map. The survey made in 1793 by Captain Alonzo de Torres {y Guerra} of the Royal Spanish Armada under orders of the Viceroy of Peru was useless as a navigational chart but added some new names to individual islands, though it is not possible in most cases to attach them correctly. The only ones of which we can be reasonably certain are Isla de Guerra [Culpepper], Isla de Nuñez Gaona [Wenman], and Santa Gertrudis [Albemarle].

§§ A General Map of the World or Terraqueous Globe. Slevin is mistaken: there are five island names; all written en español (los Hermanos, Isabella, S. Marcos, Is. de Sta. Maria, S. Clemente).

† The engraver was Vicente Fuente F.

In 1793-1794, Captain James Colnett made a chart in which the islands are placed fairly correctly in their relative positions, the first chart that could be considered workable. Arrowsmith of London printed a chart in 1798 based on Colnett's but not nearly so complete,§ as coastlines were omitted and Indefatigable, which is called Norfolk, is represented as a mere islet. Also he omitted much useful information contained in the original chart, such as places to water, careen ships and gather wood. It is noteworthy that the famous Galápagos “post office” is marked on the original chart though no mention is made of it in Colnett's log.§§

§ “[Aaron] Arrowsmith of London printed a chart in 1798 based on Colnett's ….” It is unclear what this is supposed to mean. The Arrowsmith chart appeared in Colnett's 1798 Voyage and there is no known version of anything drawn by Colnett himself.

§§ Norfolk is not “represented as a mere islet,” but is shown as the southeastern fragment of a larger island. In other words, Colnett knew the island was larger than shown on the map, but the necessary information was lacking. “Careening Place. Water and plenty of Wood” was added by Arrowsmith to the 1808 edition of the map. The post office was not marked on the original chart of 1798, but added to the 1820 edition of the map, based on information taken from an 1815 chart by John Fyffe, HMS Indefatigable. In any case, Colnett's track (see link, above) and his text both make it clear that he did not visit the island which he mis-named as Charles (the modern Isla Floreana).

In the early 1800's, three other charts of the Galápagos were made, apparently {based on} the work of Captain Colnett though none was as complete as his first one. All have the same error in the coastline of Albemarle, each one showing a large bight in the southeast corner of the island (the worst feature in Colnett's chart) which, of course, is an error and was corrected in the survey of HMS Beagle in 1835. The charts in question are those of Captain Porter of the U. S. Frigate Essex, Captain P. Pipon, R. N., of HMS Tagus, and Captain John Fyffe of HMS Indefatigable. None of them can be said to equal the original chart of Captain Colnett.

It was not until 1835 that a real survey was undertaken by HMS Beagle under the command of Captain Robert Fitzroy, R. N. This distinguished officer made a complete survey of the archipelago and produced a good navigational chart that was published by the Hydrographic Office of the Admiralty and used by all countries from the date of the survey until the year 1942, when another survey was made by the USS Bowditch. During the cruise of the Beagle, many detailed anchorages were made on the following islands: Albemarle, at Iguana Cove and Tagus Cove; Charles, at Post Office Bay; Chatham, at Freshwater Bay and Tarrapin [sic, Terrapin] Road; Hood, at Gardner Bay; James, at Sulivan Bay.

Ships of the Royal Navy going to and homeward bound from their station at Esquimault, B. C. stopped at the Galápagos to look for shipwrecked sailors on its inhospitable shores and took advantage of their visits to plot additional anchorages. In 1846 HMS Pandora surveyed Conway Bay, Indefatigable Island, and re-surveyed Post Office Bay, Charles Island, and Freshwater Bay, Chatham Island. Midshipman G. W. P. Edwardes of the Daphne made a sketch of Freshwater Bay, showing the difficulties encountered in watering on a rocky coast five miles off a lee shore, with the prevailing winds from the southeast. The British later plotted two more anchorages: Sappho Cove, Chatham Island, by HMS Sappho, and Webb Cove, Albemarle Island, by HMS Cormorant.

In addition to the islands and islets, there are several rocks which were considered worthy of names, the two outstanding ones being Kicker Rock, off the northern coast of Chatham Island, which has been referred to as “Sleeping Lion” and spoken of many times by Captain Colnett as the “remarkable rock,” and Roca Redonda, about fifteen miles off the north point of Albemarle, no doubt so named because of its shape, redonda meaning square sail.§ Both these rocks are pictured on the chart of Captain Pipon. Both Captain Colnett and Captain Porter on the Essex had difficulty with the currents setting them too close to Redonda and narrowly escaped hitting it.

§ Actually, a bulging square sail which appears to be round.

The Italian, French and United States navies also participated in mapping the Galápagos. In 1882 and 1885, the Italian corvette Vettor Pisani visited Wreck Bay, Chatham Island, and in 1887 Midshipman Estienne of the French corvette {Le} Decres plotted an anchorage at Black Beach, Charles Island. In 1909 the USS Yorktown charted Cartago Bay on the east coast of Albemarle and in 1925 a reconnaissance of Darwin Bay, Tower Island, was made by the USS Marblehead. In May, 1932, Captain Garland Rotch of the yacht Zaca, while on the Templeton Crocker Expedition of the California Academy of Sciences to the Galápagos Islands, made two sketch surveys of anchorages not yet charted, one on the northeast side of Narborough Island, which he called California Cove, and the other of Academy Bay, Indefatigable Island, locally known as Puerto Presidente Ayora.

The islands, as well as their capes and bays, have for the most part been named after the ships which surveyed them or after people connected with the history of the islands. Indefatigable has also been known as Norfolk Island after the Duke of Norfolk and as Porter's Island after Captain David Porter of the U. S. Frigate Essex. It was named Bolivia by Vilamil, who also gave the name of Olmedo to James Island. Nameless Island has been known as Bewel Rock and Isla Sin Nombre, while Isla Wolf has been applied to Wenman and Isla Darwin to Culpepper. On Albemarle Island, Bank's Bay was named after Sir Joseph Banks, the famous botanist; Essex Point was named by Captain Porter after his ship, the Essex; Tagus Cove, called Bank's Cove by Colnett, was renamed for HMS Tagus; Cape Berkeley was so called in honor of the Honorable Captain Berkeley, R. N.,§ and Cape Rose honors the memory of Jean Rose, buccaneer and companion of Edward Davis;§§ while Webb Cove is named after Lieut. G. A. C. Webb, R. N., of HMS Cormorant. On James Island, Cowan Bay (sometimes called James Bay) was named by Captain Porter in memory of Lieut. John S. Cowan of the Frigate Essex, who was killed in a duel and buried there; and Sulivan Bay is named in honor of Lieut. {Bartholomew} James Sulivan of HMS Beagle. Sappho Cove on Chatham Island is named for the ship which surveyed it, HMS Sappho. On Indefatigable Island, Academy Bay is named after the American schooner Academy, and Conway Bay after HMS Conway.

§ Probably, Admiral Sir George Cranfield Berkeley (1753–1818).

§§ It seems highly unlikely that Cape Rose (the modern Cabo Rosa) was named after the buccaneer. Neither Cowley nor Dampier mention him, and his name does not appear on any charts derived from Cowley's work. The name was probably added in recent times, perhaps as a variation on Santa Rosa (Isla Santa Cruz).

In 1892 the Republic of Ecuador renamed the Galápagos the “Archipielago de Colón” in honor of the famed mariner Christopher Columbus, and that is still the official name. The Galápagos Islands seems to be preferred, however, and is more commonly used. Most of the islands also have at least two names. The following list gives the English and Spanish names as they appear on modern charts.

Slevin's list appears here on the “Notes” page.

The last general survey of the Galápagos was made by the USS Bowditch in 1942. In this survey there was at least one major correction, the removal of the well-formed crater on Indefatigable Island, which had appeared on all charts previous to that date. It is now known that it does not exist. Since the islands were used as a military base during World War II, they have been flown over and mapped from the air and the great mountains no longer hold any secrets.

Maps

The following four maps which appear in Slevin's paper are taken from the sources indicated here.

Map1: Although the Galápagos appeared as early as 1570 on the charts of Abraham Ortelius, it was not until 1684 on the chart of Ambrose Cowley, the English buccaneer, that any attempt was made to place them in their relative positions and give the islands individual names; so Cowley's chart may be rightly called the first chart of the islands.

John Russell: map facing p. 145 in Burney's Chronological History ….

Map 2: The tracing made by Captain Alonzo Torres, of the Spanish Frigate Santa Gertrudis, although over one hundred years after Cowley, does not compare with the efforts of the English buccaneer. §

§ Alonzo de Torres y Guerra: Archipielago de Galápag os: Mapa trazado en 1793 por los marinos españoles de la fragata “Santa Gertrudis.” The map is quite similar to the other two versions of the same map, but Slevin does not identify his source.

Map 3: The chart used in 1812 by Captain David Porter, of the United States Frigate Essex, is practically a replica of the one made in 1793-1794 by Captain James Colnett, of the British ship Rattler.

William Hooker: Gallapagos Islands map in Porter's Journal of a Cruise.

Map 4: The survey made, in 1835, by His Britannic Majesty's Ship Beagle furnished the standard chart of the Galápagos used by maritime nations for over one hundred years, and with the exception of some corrections in elevations is practically the same as that made by the USS Bowditch in 1942. The only strikig alteration is the depicting of Indefatigable Island. It is now an established fact that there is no great central crater as shown on the British Chart, the top being composed of numerous volcanic cones and broken-down minor craters.

W. M. Giffen: Pacific Ocean: The Galapagos Islands.